Organizing Our Experience: Mental Models

M.C. Escher, Lizard, 1942. Wikiart.org.

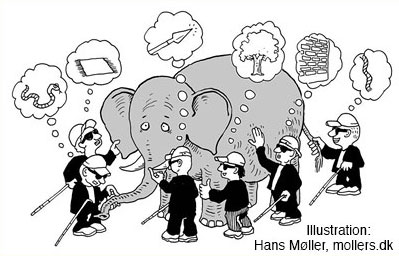

A person can view and understand the very same piece of information differently, depending on the mental model he uses to interpret it. When we hear thunder, do we explain it as the anger of the gods, the noise made by an atmospheric event, or some other phenomenon?

Mental models describe the way in which individuals organize the enormous amount of information, physical sensations, sights and sounds that we experience from moment to moment. In a sense mental models act like filters, affecting the way we see and interpret the world; or like shortcuts we use to assess, anticipate and relate to situations and events.

At a very basic level, you might organize two events into a cause-and-effect scenario, because you believe that one of them causes the other, and thereafter will expect that if the first event occurs, the second one will also occur. (If I step on a burning ember I can expect to feel pain.)

In human thought there’s likely to be an array of mental models to choose from, and which one an individual selects will affect his memory, response and expectations with regard to that information.

Mental models underlie biases and stereotypes. Consider Mary’s chances over John’s of getting a job when interviewed by someone who’s mental model is that women are more stupid or less qualified than men, versus someone who thinks that women are just as good as, or better than, men. Because of racially biased models, readers judge an essay written by John or Mary more highly than that same essay written by Jamal or Dashanique.

A person can view and understand the very same piece of information differently, depending on the mental model he uses to interpret it.

Understanding others’ unspoken mental models can be conscious or unconscious. In his book, Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do, social psychologist Claude Steele describes how the African American New York Times writer Brent Staples whistled Vivaldi while walking the streets of Hyde Park at night to signal to white people that he was educated and nonviolent.

One of our extraordinary brain’s capacities is to rapidly sort through numerous possible models, select relevant details, and keep multiple models in mind simultaneously. Humor is often based on setting up the expectation of one scenario and suddenly switching to another; or by exploiting an ambiguity.

In his book The Language Instinct, the linguist and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker gives many examples of humorously ambiguous newspaper headlines such as, “Drunk Gets Nine Months in Violin Case.” In this example the juxtaposition of two widely different interpretations (mental models) of the phrase “violin case” triggers a chuckle. We recognize simultaneously that one scenario is plausible while the other is ridiculous.

Tales of Mulla Nasrudin, one of the world’s most famous folk heroes, frequently illustrate the limitations of our mental models. In this story, the Mulla’s model of “looking where there is light” leads him to make this classic mistake.

There’s More Light Here

Someone saw Nasrudin searching for something on the ground.

“What have you lost, Mulla?” he asked.

“My key,” said the Mulla.

So they both went down on their knees and looked for it. After a time the other man asked: “Where exactly did you drop it?”

“In my own house.”

“Then why are you looking here?”

“There is more light here than inside my own house.”

From The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin, by Idries Shah.

In order to communicate, we must share a common language and enough overlapping experience to be understood. And we must also share the same mental models.

Consider the following exchange:

John asks, “Should I light the candles?” and Mary responds, “We’ll have cake and ice cream after the children have washed their hands.”

On the literal surface, Mary’s response doesn’t answer John’s yes-or-no question at all, and could be completely unrelated. However, you can come to some quite detailed, reasonable conclusions about this exchange using a particular mental model: The setting is a child’s birthday party and the candles are on a cake. John is not asking Mary if he should light the candles at all, he is asking if he should light them now. Her implied answer is that, no, he should wait until after the children have washed their hands, which he knows from past experience will take a few minutes. Then he should light them, the birthday child will blow them out, and the cake will be cut up and served with ice cream.

We could continue in this vein to make a wealth of other reasonable conjectures: John and Mary are probably adults or older children, since they seem to be in charge and are allowed to handle fire; they are likely to be relatives or friends of the birthday child; John is probably male and Mary female; there are fewer than 15 candles on the cake; and so on.

Do we know these things for sure? Certainly not, but we are hard pressed to find alternative models that produce such a plausible interpretation. If it weren’t for mental models, this brief communication would be meaningless without a large amount of additional detail spelled out explicitly.

The cognitive neuroscientist Merlin Donald believes that the mental models we are able to construct depend upon our level of awareness.

As you can see, the communicative power of two sentences is increased enormously through the use of mental models. Not just one but many models are invoked by this example: birthday parties, social conventions, child behavior, names, safety, hygiene, candles, time, and so forth. Each word or phrase generates its own scenarios which, in turn, evoke new details. And the human brain miraculously manages to sort and select among these in the blink of an eye.

The cognitive neuroscientist Merlin Donald believes that the mental models we are able to construct depend upon our level of awareness. Non-human animals capable of basic awareness can construct action or event models like cause and effect, but, since they are incapable of reflection, they are unable to conceive of mythical explanations for events or analytical theories based on rules of evidence and logic.

The First Word

The Search for the Origins of Language

Christine Kenneally

Human communication depends on the same genetic foundations as other animals. Some were born with a greater inclination to collaborate, forming the symbolic communication of language.

Numbers and the Making of Us

Counting and the Course of Human Cultures

Caleb Everett

Numbers, says Everett, are a key linguistic innovation that has distinguished our species and reshaped human experience.

In the series: The Evolution of Language

Related articles:

Further Reading »

External Stories and Videos

Straight Talk for White Men

Nicholas Kristof, New York Times

Evidence is overwhelming that unconscious bias systematically benefits whites and men.